Written Documentation and Bibliography

There is a great deal of information available on chopines and raised heels on the Internet, however, much of it is not well documented or referenced. There are a few sites which are reasonably well researched, and I list these in my Links section. Here, I will focus on information that will allow us to recreate raised heels more accurately and place them in historical context, without trying to delve into so much detail that we lose sight of the overall picture. This is intended to be a living document as well as a storehouse of my own thoughts and commentary, so I apologize if the information may not be presented in a strictly academic fashion. Additionally, there is far, far more research available than I can possibly summarize here. For more details, I strongly suggest you examine the sources that I've listed in the Bibliography.

Terminology Definitions and Discussion

As you will soon see, it is often difficult to maintain consistency when using words that are several centuries old. So, although correlating these words from their descriptions may be tricky, I intend to be as consistent as possible in my use of the words as defined below.

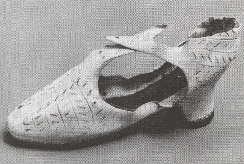

- Slippers. I define slippers as fabric or lightweight leather footwear, with one sole and made of turn shoe construction, worn almost exclusively indoors on their own. There are several accounts of slippers in both Eleanor of Toledo and Queen Elizabeth's wardrobes, as well as Spanish accounts. The Italian word for the slipper is pianelle, while the Spanish name is servilla, which Covarrubias derives from the word for "female servant" (sierva), a slipper being "light for those who have to run from here to there." Another slipper, zapatilla, is mentioned (c1524-1527) as being worn with galochas (Anderson 225). This description of a slipper is corroborated by Arnold, saying, "Slippers were low, easily slipped-on footwear, without fastenings" (214). They could be worn outdoors if some other kind of shoe was worn over them, like chopines or zoccoli (Frick 305) or pantofles, which is the reason we discuss them here. Servillas made of velvet and goatskin also existed (Anderson 225) and were likely used for the same purpose. Florio defines pianelle as "night slippers or pantofles," and pianellette as "little or thin night slippers."

There is, however, some confusion as to the use of the word pianelle. Niccoli and Landini, in Moda di Firenze describe pianelle as having a raised base, and states, with respect to the contents of Eleonora's wardrobe, that she must have possessed pianelle of various kinds since some are described differently than others (144). It is imminently possible that the recorders of the wardrobe may have made no distinction between differing styles and types of pianelle, and relied on their basic description to assist the reader. On a similar vein, Arnold says that, with respect to the wardrobes of Elizabeth, that "the warrants for the Wardrobe of Robes were written out by several clerks and detailed descriptions of footwear seem to have depended entirely on the interest and time of the individuals involved. It may simply not have occurred to one clerk to record shoes with high heels, while another would be impressed with the shoemaker's report of a new style and the technical skill involved' (216). As a result, I consider the raised slippers of Eleonora to be a kind of pantofle, and will address them in that section. However, considering Florio's definition of pianelle, the use of the word in Moda does make sense. Caroso's writing (below) clearly also refers to pianelle having a height of three fingers to a hand and a half as common.

Frick mentions that some slippers were made using a soft leather sole, called scarpe, and used for the same purpose (scarpe being the general word for shoe in Italian) (315). In Moda, these light leather slippers, which often matched the overshoes that they were put into, are scarpini (145). Florio doesn't have a definition for scarpe, but he does have definitions for scarpatore, "a shoomaker, a cordwainer," scarpare, "to shooe, to put on shooes," and is somewhat helpful with his definition of scarpini (as used in Moda) as "Scarpines, Pumps, or Sockes." English pumps, which were close fitting, single soled low shoes worn by both men and women (Arnold 213), are mentioned by Richard Percyvall, under the definition of a servilla as a "pump or pinsen to were in pantofles." Minsheu defines servillas almost in the same way, as "pinsens that women in Spain were in pantofles." The word escarpin has also been translated as pump by Percyvall, saying the escarpin is both "a kind of socke and a pumpe." This definition is supported by Minsheu's definition of escarpin as "a socke to weare on the foote, or pumps." Cotgrave defines escarpins as "pumpses; light, or single-soled shooes." The closeness of the word escarpin to scarpe cannot be easily overlooked, especially since it appears in Florio's dictionary under similar context. Rabelais, writing in 1530, uses the French word "escarpins" separately from shoes, and is usually translated as pump. A pinson, mentioned by Percyvall, seems to be a thin soled shoe or slipper (Lewis 954), and is mentioned by Stubbes as well (see below). The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) Online is not much more helpful: "A kind of thin shoe; a slipper or pump. Frequently in plural. Pinsons appear to have become obsolete soon after 1600 and no contemporary description of them is known, although there has been much subsequent conjecture. A. Way in "Promp. Parv." (1865) suggests 'possibly, high and unsoled shoes of thin leather, worn with pattens.'

Irrespective, there is a good amount of pictorial as well as written documentation for the use of scarpini,

slippers, and leather shoes with pantofles. Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe

describes many "vellat Slippers & Pantobles" as well as

"lether Showes & Pantobles," but strangely enough, there are no

details of pumps anywhere in the wardrobe, although there is a record in 1565 of

the fabrication of some pumps for the Fool, as well as Elizabeth's servant

Ippolyta the Tartarian. This, of course, begs the obvious question of what

many of the shoes seen in portraits of noble men and women. None of the

terms above adequately describes the welted, double soled shoes that the nobles

are normally thought to wear, so I will simply use the term "leather shoes."

Slippers would have been worn by both men and women, as there are accounts of

them in wardrobes of both, but probably for the same purpose, either indoors, or

worn outside with an overshoe.

- Mules. I define a mule as a low overshoe with no heel, with only

a few layers of leather to thicken the sole. It has a vamp, but no

quarters. Called chinelas in Spain they match the definition above,

and was easy to put on and take off and worn over the buskin by horseman, and were alike for both feet (Anderson 81).

There is mention of mules being ordered for Ippolyta the Tartarian, one of

Elizabeth's servants, but there is no record of Elizabeth ever having owned or

worn mules of this kind (Arnold 213). I take this to mean that these

particular shoes were normally worn by those of the serving class, rather than

nobility.

Many of the paintings and illustrations that we have also show men of rank (noblemen, dukes, doctors, etc.) in mules. Perhaps this is intended to give them the look that they need not travel outdoors, as many of the knights, soldiers, and middle class are all shown wearing shoes.

- Pantoufles. Pantuflo in Spain, pantofle in Italy, and pantoble in England. The OED defines this term as, "A slipper; a loose shoe. In early use applied to any type of indoor shoe, especially applied to high-heeled cork-soled Spanish or Italian chopins; also applied to outdoor overshoes or galoshes. In later use, a slipper, sandal, or light shoe of exotic or foreign (esp. oriental) style. From the late 15th to the mid 17th century, overshoes shaped like mules, called pantofles (pantables or pancakes), were worn to protect the front of the shoes." Having many different cognates in multiple languages, these refer specifically to raised heels made with cork, but those which are not nearly as high as chopines. Covarrubias states that this was a footwear made from cork of two or more layers. A vamp was used, as with mules and zoccoli, to keep the pantoble on the wearer. From painted evidence, the vamps could have been complete (meaning completely enclosing the front part of the foot), they could have been partial (only a band of material to hold the pantofle on) or they could have been partial and split (in which the band was held together by a ribbon or lace). Used by both men and women (Frick 305), these were constructed of wedge shaped cork bases which were covered with fine material such as velvet, silk, or leather (Anderson 228). Multiple layers or cork could be used as well, although Francesillo de Zuniga of Spain ridicules men wearing pantofles made with many layers of cork (Anderson 81). Pantofles were also very well known in England, as there are many pairs in Elizabeth's wardrobe. There are entries of "Slippers & Pantobles" as well as "Showes and Pantobles," likely indicating that they were to be made to match the slippers or shoes alluded to, and we have pictorial evidence as well. German woodcuts of a cordwainer's workshop shows examples of these pantobles as well. Stubbes discusses their use in England along with other types of shoes, and several other English writers mention them as well (see quoted section below).

- Wooden Soled Overshoes. Raised footwear designed to keep one's foot out of the mud and such has been around since at least the early 13th century, as extant examples attest to (see examples of pattens on the Pictorial page). Encompassing also the galocha in Spain, as well as the zoccoli of Italy, the main function of these shoes seems to be outdoor walking, for both men and women. Galochas are defined in Anderson by Corominas as overshoes with soles of wood and a band over the instep (228), which one must take into account not to confuse with the modern definition of galoshes, which are overshoes which goes over the entire foot and shoe worn inside them. This type of footwear was called zueco, and Covarrubias tell us that "The zueco was a footwear particular to the comedies, as those of city people and the ordinary...the zuecos are certain kind of chapines (clogs), with the covering of the entire foot, like the old women, the sisters, and religious people use. Accordingly, these style of complete shoes certainly existed, but seems to be attributed to the working and religious classes. Zoccoli, the term still in use today, have a similar definition from Frick (319-320), and the term was used to describe some chopines which were not as high or fashionable (305). Florio's 1611 dictionary describes Zoccoli as "wooden pattins, startops, galoshes or chopinos, so called because they are made of a Zocco," a zocco being a log, branch, or stump. Startups, mentioned by Florio, seem to be rough leather shoes worn as protective coverings for outdoor use, as they are rough shoes, not normally worked with the same attention to detail as other footwear of the time. The OED says, "Originally, a kind of "high-low" or boot, worn by rustics; in later use, a kind of gaiter or legging. In John Baret's Alvearie in 1573, he defines a startup as 'a high shooe of rawe leather called a stertvp.' " They don't seem to be a raised heel from the evidence, so we leave them aside at this juncture.

Florio also defines zoccoli a scacca faua - "a kind of galoshes or chopinoes, open in the midst, tied with ribands, and close at the heels." Possibly, these could be a thick patten like overshoe with both a vamp and an additional heel piece, while the normal zoccoli would probably only have had the vamp. Zoccoli are also mentioned in Moda, where their wedge shaped wood is described as legniacci, from the word legno, which refers to "any kind of wood," from Florio. The clarification between the terms zoccoli and chopine is difficult, especially because I have been unable to find the word chopine or any other cognate in any Italian dictionary of the time as yet, which leads me to believe that these types of raised overshoes were called zoccoli in Italy, regardless of their base material. The taller zoccoli would have been covered with some kind of surround material, but not necessarily. The vamp could also have been nailed into the side of the wooden wedge, and there is one extant portion of a galocha which shows this method of construction. In Moda, an interesting form of overshoes is mentioned in which a shoe is actually attached to the slipper, and this complete item of footwear was easier to wear, especially for the children. Several pairs of these types of overshoes are registered in the Guardaroba (145). I am willing to let the definitions stated above and below overlap somewhat, since clearly, elements of each might be present in one work or another, making it difficult to assign the perfect term.

- Chopines. Typically Made of either cork or wood, there are many different cognates such as cioppini, chapin and chapineys. In what seems to be footwear exclusively to ladies, these refer to tall platform heels worn frequently by Venetians as well as Spanish ladies. The OED defines this as "A kind of shoe raised above the ground by means of a cork sole or the like; worn about 1600 in Spain and Italy, esp. at Venice, where they were monstrously exaggerated. There is little or no evidence of their use in England (except on the stage); but they have been treated by Sir Walter Scott, and others after him, as parts of English costume in the 17th c."

Frick comments that "Chopine is a term of uncertain provenance that referred to this higher feminine style favored by Florentine women in the Quatrocentro. In the Cinquecento, chopines became infamous due to their use by Venetian courtesans (and others)..." (305) Minsheu defines chapin demuger as "a womans shooes, such as they use in Spain, mules, or high corked shooes." Also covered with silk, velvet, or leather like pantofles, Anderson writes that chopines could have been richly adorned with precious metals and gems, as well as embroidery, gilding, and painting, as the pictorial evidence shows. The height in Spain did not reach nearly high as those in Venice, but pairs being a hand were not uncommon, as extant Spanish examples show. Both Covarrubias and Talavera, writers of the time period, agree that a chopine could add an elbow length to a woman's height, and Juana de Aragon had a pair of chopines at the beginning of the 16th century that were a foot high (229-235). Extant examples as well as descriptions also prove the extremes of height (see the Pictorial page and below). The chopines also differed between Italy and Spain, in that Italian models (mostly, if not all, Venetian) were more ornately carved and shaped, while the Spanish ones being were more basic in geometry, but just as opulently decorated. Anderson states that servillas and chopines were given as gifts by husbands to their wives, again evidencing that they were worn together (225). As mentioned before, I was unable to find a reference to chopines (or any variant thereof) in any Italian dictionary of the time currently available to me. Obviously, he knew of it, because he mentioned "chopinoes" in his definition for zoccoli, but for a fashion that was popular in Italy, specifically Venice, it is interesting to note. Cassell's 1919 dictionary defines chopine as being derived from the Spanish chapa, a metal plate. Indeed, some Spanish chopines did have a metal plate wrapped around the lower part of the cork base (possibly to keep the layers of cork more stable), but this particular connection seems too tenuous. This metal plate seems to have been, in some cases, gilded and ornamented. Covarrubias defines the term alcorque, saying, "A kind of footwear, whose soles were lined/faced in cork, that as we have said is the bark of the cork oak, said in Arabic corque, and with the article alcorque." He goes on to tell of an interesting tale (see full text below) of their being invented to prevent women from spending time in the company of other men. He says that, being first made of wood, they were very heavy, and that the ingenuity of the women overcame this inconvenience by substituting cork. It is important to keep in mind that a cork tree looks a great deal like an oak tree, which is why we use the term "cork oak." Still, they needed the support of others to even walk a short distance outdoors, as many authors and paintings show. The line of thinking in which chopines were used to curb a woman's mobility is also present in other sources, as Anderson mentions above. Other sources (see below) also touch on this point.

As mentioned before, although there are many references to cork being used in the manufacture of chopines, wood was also used. Frick, when discussing zoccoli, describes them as being made primarily out of white poplar (319) which makes sense, considering poplar is strong, yet relatively light wood, and easy to carve. Hazlitt, citing Samuele Romanin who write the Storia documentata di Venezia, in Tomo 4, p495, says, referring to chopines, "They were frequently made of the Lombardy poplar. They have long been discarded." (751) I have been unable to verify this reference as yet. Samuel Weller Singer, writing in 1826 on Shakespeare's literature, says that, "Covarrubias asserts that in Italy, they were made of zapino, and not of cork." Florio defines the term zapino as "the Fir-tree," so the statement is feasible, but I have been unable to verify this in Covarrubias. As far as the covering goes, velvets and leather were certainly used to a large extent, but there are a couple of extant pieces in which patterned brocades were also used. In terms of covering, although some of the velvets were placed on or near bias, not all of them were. The brocades that are used in some extant examples of chopines may also have been placed on the bias of the ground in order to give it more stretch.

Outside of Venice and Spain, tall zoccoli or chopines did not seem to

be very popular, as many writers of the period tell us, but raised overshoes

were certainly worn, albeit at a much more modest height than those in Venice.

Chopines did not seem to be popular in England or France either, especially when

considering much of the available writing, but they seem to have been used on

occasion and were certainly known. Some English theatre productions used them to

allow small boys to appear taller while they played the part of women. See

Hamlet's witty remark in Act II, Scene II, line 43: "Thy face is valiant since I

saw thee last: Com'st thou to beard me in Denmark? By'r Lady, your ladyship is nearer heaven than when I saw you last by the altitude of a chopine!

Pray God, your voice, like a piece of uncurrent gold, be not cracked within the

ring." These three statements seem to poke fun at the boys who played

females in plays of the time, and they give us some insight into their use. The first

jests on the matter that the boys might have just been starting to show a beard,

which is certainly feasible.

The second seems to indicate that the boys would have been wearing chopines of

some sort to allow them to account for their height difference between them and

the other actors in the production. The third pokes fun of their voice

cracking as they reached puberty by likening it to a coin - if a piece of gold

currency was cracked, then it would be debased (i.e. uncurrent gold). The

jest

is clearly meant to provide not only an instance of the use of the word in

question, but also an account of the use of the chopine in the theatre (Walsh

189). Chopines also seem to have been used in some formal occasions. When Lady Jane Gray was presented in 1553 to begin her short reign as queen, to make her appear taller and more commanding,

she was given chopines to wear.

A description of this presentation was made by a contemporary writer, Sir Baptist

Spinola, a Genoese merchant living in Italy at the time: "The new queen was mounted on very high chopines

[clogs] to make her look much taller, which were concealed by her robes, as she

is very small and short." (Davey 253)

As far as their use, there is a great deal of references on the Internet which state, without any

documentation or references, that chopines were used by prostitutes to allow them

to appear taller and more obvious to their potential clients. Simply do an

Internet search, and you will find this to be so. However, some sources of the

time specifically say that this footwear was not worn by courtesans (see

below) and was used by ladies of rank. My personal conjecture: The patrons of these courtesans would have been

wealthy noblemen, able to afford and lavish fine gifts upon these appreciated

women.

So much so, that a courtesan might very well be confused for a wealthy noblewoman, and

vice versa. In fact, there is a painting in the Bibliotheque Nationale

de Paris, France, which shows three seemingly identical women: a Venetian Bride, a Venetian Matron, and

a Venetian Courtesan (my

thanks to Elizabeth Bernhardt for this reference). So, it makes sense to

me that writers of the period might say that courtesans did not wear them (i.e.

they were not supposed to and were reserved for ladies of rank), but because

this conspicuous finery was so generously donated to them by their patrons, and considering the fact that these

noble men enjoyed the company of these ladies, they would have had no desire to

construct any barrier to said enjoyment. As a result, it doesn't seem so farfetched

to believe that these nobles were facilitating the courtesan's ability to follow this

particular fashion. Gifting a new wife with slippers and chopines was

mentioned earlier, but Anderson also cites the same reward of a friar to his

night's companion, the daughter of a sacristan (225). All of this seems to

belie the idea that one wore chopines to

flaunt one's availability. If this were the case, then noblewomen everywhere

would have been in trouble!

Interestingly, if one examines the paintings of the Spanish and Italian chopines more closely, it is clear that from the length of the skirts, that the chopines were meant to be seen, and were ornately decorated, both gilt and painted. However, aside from states of deshabille and when a toe of the chopine is escaping from the skirts, sometimes you can only tell that a particular lady is wearing chopines because of her massive height and the way that she holds to the hands of her servants (I have yet to see anyone actually resting their hands on shoulders or even heads of their servants). Based on this evidence, Semmelhack proposes that the Italian chopines may have been part of the "underwear" of a Venetian noble lady, which is certainly plausible.

Additionally, there seem to have been some more modern terms to further classify specific types of chopines. The term "zibroni" does not appear in Florio's dictionary, but it seems to be a more modern term to refer to chopines, specifically the kind of chopine that is very narrowly waisted, such as that in the extant examples section (see Semmelhack for more details). Additional terms that do not appear in Florio's dictionary, but are classified by Semmelhack, are zibroni (referring to chopines that are very waisted and stand on a round base - see the extant page for an example), and calcagnini (the tall, nobbled based chopines, again see the extant page). Although these terms do not appear in the dictionary of the time, the word "calcagno," meaning "a heele of a man" does. Perhaps it was a bit of wordplay on the part of the person who came up with the word.

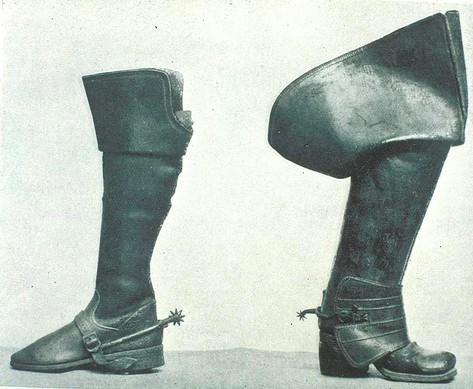

- Buskins. Buskins, which were a kind of "half boot" reaching just above

the calf, were popular both in Spain and England. The OED defines them as

"A covering for the foot and leg reaching to the calf, or to the knee; a

half-boot. Also the high thick-soled boot (cothurnus) worn by the actors in

ancient Athenian tragedy; frequently contrasted with the "sock" (soccus), or low

shoe worn by comedians." Constructed of very thin goatskin or sheepskin, they seem to be made with turnsole construction, and were very close fitting to the leg.

(Anderson 227) They could also have been made with velvet and were

frequently lined (Arnold 215). Quoting Covarrubias, "Of him who is easy in his opinions that he can be swayed by anyone, it is said that he can be turned like a buskin..." Anderson also talks about wearing boots, pantofles, or even another set buskins over one pair of buskins, like the Duke of Bejar did in 1525, riding to Portugal with boots covering two pairs of buskins. Prince Juan in 1496 wore pantofles with buskins to meet his Austrian bride Margarita, and Phelipe el Hermoso was

dressed in buskins and shoes after his death in 1506. Cunnington, writing in England during the early 16th century, described buskins as "usually softer [than the boot]...made of Spanish leather or velvet, and sometimes lined with fur-lamb or coney."

(79) Buskins could have been plain (with no slits for lacing), with a lacing (perhaps only partially laced), and

completely laced (likely, slit all the way up the inside or outside). The buskin could also have been sewn closed. A book on horsemanship in 1600 by Vargas Machuca speaks about the buskin: "A buskin foot must fit tightly, because it looks better and is readier for whatever may happen. The entrance and the instep should be wide, because this is becoming to a foot in the stirrup. The calf must be tight in order not to slide down. It should be closed to the top and not rise above the knee." The same book also says that "white buskins go with any trappings save those of mourning, if the white is good and the flesh side is turned outward (Anderson 80). Many shoes and boots were beginning to be made with the flesh side outwards. Although buskins are not

necessarily a form of raised heel, I include them here because they were often worn with raised heels.

Elizabeth wore many pairs of buskins in the 1560s, and their mention seems to

fit the description above (Arnold 216). Arnold goes on to say that

by the end of the 16th century, the term had become archaic and was then used to

describe actor's boots and footwear of the type worn in masques, and that the

final pair mentioned in the accounts in 1592 may very well have been used for

that purpose. There is, however, an extant pair of what are normally

called buskins worn by Elizabeth c1600, but these do not fit our description of

the typical buskin, so we will discuss these in the section on raised boots.

- Raised Shoes.

There are many apocryphal references of how Catherine de Medici allegedly "invented high heels" and wore them in 1533 at her wedding to Henri II to become the

queen of France, but I have been unable to locate a

contemporary account to give mention of the wedding or description of her

footwear. Per personal conversation with Semmelhack, of the Bata, she also has been unable to find any historical reference to support this claim, which supports the conclusion that this reference is simply apocryphal. Additionally, Hurlock, contrary to much of the anecdotal claims, says that it was Queen Claude, wife of

Francois I (they married in 1514), who first introduced raised heels into France

from Spain, not Catherine de Medici from Italy. Likewise, I have been unable to find

any more evidence on this theory. On a side note, A 19th century author, Elizabeth Sewell, mentions a

contemporary author of the 1570s who alludes to Henri III's the new queen,

Louise de Vaudemont, and writes of Louise that, "...her majesty has no need to wear

high-heeled shoes to increase her height."

Delving deeper, there are a few theories on how heels evolved in European dress. There seems to be little debate

that shoes with a bona fide heel did not come about in Western dress until the end of the 16th Century. However,

the inspiration for those heels is a subject of animated debate, the result of which is still unclear. This is not intended as an exhaustive text; however, I will briefly

discuss the current theories, but for more information, please visit the Bibliography section, and do visit the Crispin Colloquy, specifically the archives for the discussion of the origins of the heel (http://www.thehcc.org/discus/messages/4/1003.html?1282667447).

Ms. Swann states that there are 2 origins for 2 types of heels (I have made minor editorial changes for the sake of clarity):

"1. Platform soles with insole higher at back (i.e. a covered wedge heel), which start just after 1400. These evolve into a kick-up under-arch in the 16th century - see the image of Queen Elizabeth's 1595 'heels with arches' in the Paintings and Sketches section for more details. There are also 1 or 2 inserted lifts on flat shoes, to give the same effect by at least 1545, from, e.g., the shoes found in the 'Mary Rose' wreck.

2. Repair patches, being used practically forever, become stacked heels soon after, in the form of 1601 'Polony' (Polish & high) heels. The main reason for all this happening is that the height of Spanish chapin (2 1/2-3" from the same 1400) was being exaggerated late 16th c. in Italian zoccoli, what Shakespeare 1601-2 called chopine. Women not wearing them wouldn't want to look lower than those who did, never mind how much it upset men."

An alternate theory is offered by Ms. Semmelhack (again, some minor editoral changes made):

"Based on an extensive review of evidence from the Near East dating from the 14th-15th c, it is possible that Persian heels may have inspired the Western fashion for heels for myriad economic and political reasons that have to do with the rise of European interest in Persia at the end of the 16th century. I believe that there can be no question that it originated somewhere in the Near East centuries before the concept was embraced in the West. One only has to look at the plethora of Near Eastern paintings that date to the 14th and 15th centuries. I have even seen a 10th century Persian bowl decorated with an image of horse and rider where the rider is clearly wearing a heeled riding boot. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 65.1278)."

The popular opinion that heeled shoes were innovated for purposes of horsemanship does not seem to hold much water - people have been riding horses for centuries without any need for hels. However, Ms. Semmelhack makes an excellent point in the heel's role in riding horses, and certainly, there is no argument today that a heel makes riding easier:

"Why the heel was innovated is certainly open for debate, however, the argument that one can ride a horse without wearing heeled footwear and therefore heeled footwear has nothing to do with riding can be likened to an argument against linking the invention of the fork for eating. One can certainly eat without a fork, as was done for centuries before the invention of the fork, but that doesn't negate the fact that the fork was invented as an aid to eating."

Indeed, it is certainly possible that a combination of these two theories may have been responsible for the overall gradual evolution of the heel, but manifest in different ways. Stacked leather heels, which used through the centuries and became the most common method of crafting men's heels in the later third of the 18th century. However, heels were commonly made of timber for both men and women, although in order to obtain a fashionable shape, starting in the 17th century, ladies' heels were almost exclusively made of timber.

- Discussion of QEWU and the mentions of heels in wardrobe accounts

- Raised Boots. Along with the development of the heel, incorporation of the heel into boots came shortly after. In the 16th century, there isn't a great deal of documentation for boots - they were mainly relegated to the horseman, being high wear footwear for hard riding, and not for softer, gentler wearing like the buskins mentioned above. In the 17th Century, boots became fashionable, and were commonly worn in place of shoes. In terms of construction, the heel of a boot follows similarly to that of a raised shoe. Stacked leather seems to be the most common heel construction from the sheer number of examples. Looking again towards raised shoes, Semmelhack's theories regarding the Near East influence seem to apply to boots as well, as many of the horsemen are wearing heeled boots.

Relevant Writings of the Time Period

Here, I compile a listing of commentary from different writers of the time period with respect to raised heels. By no means is this a comprehensive list, as many writers have had something to say about the subject. However, I have tried to screen it in such a way so that the writing is still within the scope of this endeavor.

If you have a writing that you think would be appropriate to this listing,

please do write me with where you found it, and I'll include it here.

I've organized these writings by date.

In Pietro Casola's Journey to Jerusalem, when passing through Venice in 1498 (he was Milanese), wrote, "...the

pantobles or zilve, as they were called, were worn so monstrously high, that ladies in the streets were obliged to save themselves from tumbling by leaning on the shoulders of their

lacqueys..." (Here, the word I have translated as pantobles is pianelle

in the Italian. It has been translated by Hazlitt as "pattens." An

argument could be made for both.) (Hazlitt 751)

Around 1530, Rabelais wrote his satire, Five Books of the Lives, Heroic Deeds, and Sayings of Gargantua and his son Pantagruel, he mentions the use of pantofles and such in his description of the clothing of the men and women in the religious order of Theleme: "Their shoes, pumps [the French word here is escarpins], and slippers [pantoufles] of red, violet, or crimson-velvet, pinked and jagged..." (Rabelais, Book I, Ch 1.LV.)

Around 1544, Castiellejo wrote a poem (page 390), translated by Anderson:

When women are come to pray

Or to chant the morning hymns,

Their chopines frequently

Go flying off and stray

Into the choir.

The below letter, in the Genoese Archives, is from Sir Baptist Spinola, a very rich Genoese merchant who flourished in London under Edward VI (by whom he was knighted), Mary, and Elizabeth. Frequent mention of him will be found in the State Papers of this period. On one occasion, Elizabeth paid him an enormous sum - probably for supplies of Genoa velvet and brocade. He describes the presentation of Lady Jane Gray on July 10, 1553: "To-day [the date is not given, but possibly it figured on the cover now lost : it was, of course, 10th July 1553] I saw Donna Jana Groia [an Italianization of Jane Grey] walking in a grand procession to the Tower. She is now called Queen, but is not popular, for the hearts of the people are with Mary, the Spanish Queen's daughter. This Jane is very short and thin, but prettily shaped and graceful. She has small features and a well-made nose (ben fatta ha il naso), the mouth flexible and the lips red. The eyebrows are arched and darker than her hair, which is nearly red. Her eyes are sparkling and red [rossi - a sort of light hazel often noticed with red hair]. I stood so long near Her Grace, that I noticed her colour was good, but freckled. When she smiled she showed her teeth, which are white and sharp. In all, a graziosa persona and animata [animated]. She wore a dress of green velvet stamped with gold, with large sleeves. Her headdress was a white coif with many jewels. She walked under a canopy, her mother carrying her long train, and her husband Guilfo [Guildford] walking by her dress all in white and gold, a very tall strong boy with light hair, who paid her much attention. The new queen was mounted on very high chopines [clogs] to make her look much taller, which were concealed by her robes, as she is very small and short." (Translation and Notes from Davey 252-3)

John Stubbes, in his 1583 Anatomy of Abuses writes, with respect to men's shoes:

Philo: To these their nether-stocks, they have corked shooes, pincnets, and fine pantofles, which beare them up a finger or two inches or more from the ground; wherof some be of white leather, some of black, and some of red, some of black velvet, some of white, some of red, some of green, raced, carved, cut and stitched all over with silk, and laid on with golde, silver, and such like: yet, notwithstanding, to what good uses serve these pantofles, except it be to wear in a private house, or in a man's chamber to keepe him warme? (for this is the onely use wherto they best serve in my judgement) but to go abroad in them, as they are now used al together, is rather a let or hinderance to a man then otherwise; forshall he not be faine to knock and spurn at every stone, wall or post to keep them on his feet? wherefore, to disclose even the bowels of my judgement unto you, I think they be rather worne abrode for nicenes, then either for any ease which they bring (for the contrary is moste true), or any hansomnes which is in them. For how should they be easie, when [a man can not goe steadfastly in them, without slipping and sliding at every pace ready to fall doune: Againe how should thei be easie where] as the heel hangeth an inch or two over the slipper on the ground? Insomuch as I have knowen divers mens legs swel with the fame. And handsome how should they be, when as with their flipping and flapping up and down in the dirte they exaggerate a mountain of mire, & gather a heape of clay & baggage together, loding the wearer with importable burthen.

Spud: Those kinde of pantoffles can neither be so handsome, nor so warme as other usuall common shoes be, I think. Therefore the weringe of them abrode rather importeth a Nicenes (as you say) in them that weare them, that bringeth any other commodytie, els unlesse I be deceived."

(Stubbes 57-58).

Stubbes continues to rail against women's shoes:

Philo: ...whereto they have korked shooes, pinsnets, pantoffles, and slippers, some of black velvet, some of white, some of greene, and some of yellowe; some of Spanish leather and some of English leather, stitched with silk, and imbrodered with Gold and solver all over the foote, with other gewgawes innumerable. All which, if I should endeuoure my selfe to expresse, I might with more facilitye number the sands of the Sea, the Starres in the skye, or the grasse uppon the Earth, so infinit and innumerable be their abuses. For weare I never soe experte an Arithmetician, or Mathematician, I weare never capable of the halfe of them, the devill brocheth soe many new fashions every day.

(Stubbes, 77)

In George Puttenham's The The Art of English Poesy in 1589, he writes, "These matters of great princes were played upon lofty stages, and the actors thereof are upon their legges buskins of leather called Cothurni, and other solemn habits, and for a speciall preheminence did walke upon those high corked shoes of pantofles, which now they call in Spaine and Italy Shoppini." (Puttenham 86)

Also in 1589, from Thoinot Arbeau's "Orchesographie," we have a discussion between a dance master (Arbeau) and his student (Capriol):

CAPRIOL:

The Poles, so I have heard said, invariably walk on their toes.

ARBEAU:

Their heels are raised and supported by the cork and iron placed in their shoes, which prevents them from running as easily as we do. That is why the Poles give the appearance of being to or three fingers taller than they are.

Fynes Moryson, who was in the area from 1591-1597, writes in An Itinerary containing his Ten Yeeres Travel..." writes, "the women of Venice weare choppines or shoes three or foure hand-bredths high, so as the lowest of them seeme higher then the tallest men, and for this cause they cannot goe in the streetes without leaning on the shoulder of an old woman. They have another old woman to beare up the traine of their gowne, and they are not attended with any man, but onely with old women. In other parts of Italy, they weare lower shoos, yet somewhat raised, and are attended by old women, but goe without any helpe of leading." (Moryson 220)

Cosmo Agnelli, in 1592, wrote Amorevole aviso circa gli abusi delle donne vane, or in English, Loving Advice on the Abused of Vain Women. Agnelli had been issuing Christian warnings on how women were to behave for at least sixteen years previous to this work, and in it, he calls out the wearing of high-heeled shoes as one of the three cardinal abuses to avoid, including hair coloring and styling, and painting and exposing your breasts: "Women think that strutting around from this magnificent perspective makes them alluring, but true beauty always consists in proper proportions. Elongating your legs with heels that are a quarter or even half an arm's length leaves you looking like a monster, with the head and torso of a child perched on the legs of a giant. What beauty can there be in having your knees nearly where your chin should be, in being unable to take four steps without danger of imminent collapse, in tumbling over should you try to kneel, and being unable to arise without assistance? How does it look in church when, at the moment the priest raises the holy sacrament, there you are standing in pompous arrogance while you should be prostrate on the floor? God sees everything. Back at home, high heels prevent you from attending to the household chores any good wife and mother should be doing." (Bell 205-6)

Joseph Hall, in his Virgidemiarum, Six Books of Satires, in 1598 writes in Book IV, Satire VI, with respect to the British ladies of Elizabeth's time: "When comelie striplings wish it were their chance for Cenis' distaffe to exchange their lance Curl'd periwegs, and chalked their face, And still were poring on their pocket glasse. Tyr'd with pin'd ruffles, and fans, and partlet-strips, And buskes and verdingales about their hips; And tread on cork stilts, a prisoner's pace..." (Hall, IV.vi)

Fabrito Caroso, in his 1600 dance manual Nobilita di Dame, writes on the importance of wearing chopines properly. However, we must take note that the actual Italian word he uses is "pianelle." See the section above on slippers. "Some ladies and gentlewomen slide their chopines along as they walk, so that the racket they make is enough to drive one crazy! More often they bang them so loudly with each step, that they remind us of Franciscan friars [referring to the zoccolanti defined in Florio as "certain Franciscan friars that goe on high woodden pattens or startops"]. Now in order to walk nicely, and to wear chopines properly on one's feet, so that they do not twist or go awry (for if one is ignorant of how to wear them, one may splinter them, or fall frequently, as has been and still is observed at parties and in church).....By walking this way, therefore, even if the lady's chopines are more than a handbreadth-and-a-half high, she will seem to be on chopines only three fingerbreadths high, and will be able to dance flourishes and galliard variations at a ball, as I have just shown the world this day." (Caroso 151)

Shakespeare's Hamlet, written around 1600, has Hamlet making a witty remark: "Thy face is valiant since I saw thee last: Com'st thou to beard me in Denmark? By'r Lady, your ladyship is nearer heaven than when I saw you last by the altitude of a chopine! Pray God, your voice, like a piece of uncurrent gold, be not cracked within the ring." (Hamlet Act II, Scene II, line 43)

In John Marston's Dutch Courtesan, 1605, one of the characters asks, "Dost thou not wear high corked shoes - chopines?" (Marston 147)

Thomas Coryat describes chopines in his Crudites, written in 1611: "There is one thing used of the Venetian women, and some others dwelling in the cities and townes subject to signiory of Venice, that is not to be observed (I thinke) amongst any other women in Christendome: which is so common in Venice, that no woman whatsoever goeth without it, either in her house or abroad, a thing made of wood and covered with leather of sundry colors, some with white, some redd, some yellow. It is called a chapiney, which they wear under their shoes. Many of them are curiously painted; some also of them I have seene fairly gilt: so uncomely a thing (in my opinion) that is pitty this foolish custom is not cleane banished and exterminated out of the citie. There are many of these chapineys of a great height, even a half a yard high, which maketh many of their women that are very short seeme much taller than the tallest women we have in England. Also I have heard that this is observed among them, that by how much the nobler a woman is, by so much the higher are her chapineys. All their gentlewomen and most of their wives and widowes that are of any wealth, are assisted and supported eyther by men or women, when they walke abroad, to the end that they may not fall. They are borne most commonly by the left arme, otherwise they might quickly take a fall. For I saw a woman fall a very dangerous fall, as she was going down the staires of one of the little stony bridges with her high Chapineys alone by her selfe: but I did nothing pitty her, because shee wore such frivolous and (as I may truely terme them) ridiculous instruments, which were the occasion of her fall. For both I my selfe, and many other strangers (as I have observed in Venice) have often laughed at them for their vaine Chapineys." (Coryat 36-37)

Francois Pyrard wrote in 1611 in his visit to Portugese India. Speaking of the women: "They never wear stockings. Their gowns and petticoats trail upon the ground: their pattens, or chapins, are open above, and cover only the soles of their feet; but they are all broidered with gold and silver, hammered in thin plates which reach over the lower surface of the chapin, the upper part being covered with pearls and gems, and the soles half a foot thick with cork." (De Bergeron 102)

Also in 1611, we have Covarrubias y Orozco's, Tesoro de la lengva castellana, o Espanola, 1674 edition available at the Cervantes Virtual Library, from which Dr. Kathryn Wood was very good to translate the important sections:

Servillas: footwear, calcada [slippers] of one sole, very appropriate for the serving girl and as such have the name of 'servants' or 'of those who serve', because the others that do not have to walk with such [desembolsar = to pay out, but I'm not sure how to translate 'desemboltura,' perhaps urgency is appropriate], wear chapines, zuecos [sabots], chinelas [slippers, translated as mules by Anderson], and mulillas [mules]."

Pantuflo: footwear of old people of 2 or more corks: it is a French name, "pintoufles", Latin "crepida".

Alcorque: kind of footwear, whose soles were lined/faced in cork, that as we have said is the bark of the cork oak, said in Arabic corque, and with the article alcorque. In Latin it is called 'soccus' and from there sueco and zueco. this footwear, although it raises up the height of a person, it was not so high as the proper "cochurno" [This seems to be the Greek raised heel, of which pictures are available in the pictorial page] of the tragedies, for the reason that they represent Eros and Kings, and grave personages. The zueco was a footwear particular to the comedies, as those of city people and the ordinary: [agora?] the zuecos are certain kind of chapines (clogs), with the covering of the entire foot, like the old women, the sisters, and religious people use, which do not want others to see the [panta? my best guess is that it's the leg part of the boot] of the botin [high shoe] or servilla. To walk in zuecos, is to [rraer = raer = scrape or smooth] chapines (clogs), very high, because with them one walks poorly and disgracefully. A fable is told, that in a certain Province the women were very fast walkers/ fond of walking/ restless [andariegas] and never stopped in the house; and entering into counsel the men asked the one among them who was most wise and prudent: in order to get rid of this [habit?], he persuaded them to make footwear from wood, that would raise the women in stature, with that they would appear better, and would be more respectable. To this alludes that which says in the book of Saint Ambrose De Nabuch, Chapter 5 that the chapines serve as hindrances to women. They took his counsel; but the women made them delay, in that it was determined to look for a light wood for this and thus they asked the cork oak tree [alcornoque is the word used here] for its bark; that for this effect it was stripped many times; and they went out thus arranged, and for being seen, more fond of walking: and since then? There are no young women, and they deny nature, mend with art, notwithstanding the place of San Lucas, chapter 12.

James Howell, in 1618, in his Familiar Letters of James Howell, speaking of the Venetian women, "They are low and of small statures for the most part, which makes them to rayse their bodies upon high shoes called chapins, which gave one occasion to say that the Venetian ladies were made of three things, one part of them was wood, meaning their chapins, another part was their apparrell, and the third part was a woman; The Senat hath often endeavour'd to take away the wearing of those high shooes, but all women are so passionately delighted with this kind of state that no law can weane them from it." (Douce 457)

John Evelyn wrote in his Diary as he traveled through Sienna in 1646: "It was now Ascension-week, and the great mart, or fair, of the whole year was kept, every body at liberty and jolly; the noblemen stalking with their ladies on choppines. These are high-heeled shoes, particularly affected by these proud dames, or, as some say, invented to keep them at home, it being very difficult to walk with them; whence, one being asked how he liked the Venetian dames, replied, they were mezzo carne, mezzo legno, half flesh, half wood, and he would have none of them...Thus attired, they set their hands on the heads of two matron-like servants, or old women, to support them, who are mumbling their beads. It is ridiculous to see how these ladies crawl in and out of their gondolas, by reason of their choppines; and what dwarfs they appear, when taken down from their wooden scaffolds; of these I saw near thirty together, stalking half as high again as the rest of the world. For courtezans, or the citizens, may not wear choppines, but cover their bodies and faces with a veil of a certain glittering taffeta, or lustre, out of which they now and then dart a glance of their eye, the whole face being otherwise entirely hid with it: nor may the common misses take this habit; but go abroad barefaced." (Hazlitt 756)

John Raymond, in his Mercurio Italiano, in 1647 writes: "This place [Venice] is much frequented by the walking may poles, I meane the women. They weare their coats halfe too long for their bodies, being mounted on their chippeens, (which are as high as a man's leg) they walke between two handmaids, majestickly deliberating of every step they take. This fashion was invented and appropriated to the noble Venetians wives, to bee constant to distinguish then form the courtesans, who goe covered in a vaile of white taffety." (Douce 457)

Richard Lassels, visiting Venice in 1650, writing in his Voyage of Italy, on the Venetian ladies, remarks: "As for the women here, they would gladly get the same reputation that their husbands have, of being tall and handsome; but they overdo it with their horrible cioppini, or high shooes, which I have often seen to be a full half yard high. I confess I wondered at first to see women go upon stilts, and appear taller by the head than any man ; and not to be able to go any whether without resting their hands upon the shoulders of two grave matrons that usher them ; but at last I perceived that it was good policy, and a pretty ingenious way either to clog women at home by such heavy shoes, or at least to make them or able to go either far, or alone, or invisibly." (Maugham 135)

John Bulwer in his Artificial changeling, in 1653, complains of this fashion "as a monstrous affection," and says that "his countrywomen therein imitated the Venetian and Persian ladies." (Caldecott 63)

An Act of Parliament, in 1670 states: "Be it resolved that all women, of whatever age, rank, profession, or degree; whether virgin maids or widows; that shall after the passing of this Act, impose upon and betray into matrimony any of His Majesty's male subjects, by scents, paints, cosmetics, washes, artificial teeth, false hair, Spanish wool, iron stays, hoops, high-heeled shoes, or bolstered hips, shall incur the penalty of the laws now in force against witchcraft, sorcery, and such like misdemeanours, and that the marriage, upon conviction, shall stand null and void." Note that I have been unable to find this act of Parliament in searching through the records. Others I have spoken to have likewise been unable to find this same record, so it could be spurious.

Alexandre-Toussaint Limojon de Saint Didlier, a lively French writer on the republic of Venice in 1670, mentions a conversation with some to the doge's counsellors of state on this subject, in which it was remarked that smaller shoes would certainly be found more convenient; which induced one of the counsellors to say, putting on at the same time a very austere look, pur troppo commodi, pur troppo. (Caldecott 63. Translation of the Italian through personal communication by Helou: unfortunately useful, unfortunately.)

I have consulted a number of sources in this research, and more will be added to the list as I continue to populate this repository for information.

Anderson, Ruth Matilda. Hispanic costume, 1480-1530.

Arnold, J. A Handbook of Costume. London, Macmillan, 1973.

Arnold, J. Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlocked. Maney, Leeds, 1988.

Ashcom, B.B. By the altitude of a chopine. Homenaje a Rodriguez-Monino. Vol. I, p.17-27. 1966.

Babington, Gervase, Thomas Neogeorgus, Barnabe Googe, Frederick James Furnivall. Phillip Stubbes's Anatomy of the Abuses in England in Shakspere's Youth, A. D. 1583 1877

De Bergeron, Pierre, Jerome Bignon, Francois Pyrard, Albert Gray. The Voyage of Francois Pyrard of Laval to the East Indies, the Maldives, the Moluccas and Brazil. Ed.1887.

Bell, Rudolph. How to Do It: Guides to Good Living for Renaissance Italians. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Bernhardt, Elizabeth. Chopine Website at http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~ebernhar/index.shtml

Carlson, Mark. Footwear of the Middle Ages at http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/shoe/SHOEHOME.HTM

Caroso, Fabrito. Nobilita di Dame. Trans. Julia Sutton. Oxford University Press, 1986.

Cervantes Virtual Library - http://www.cervantesvirtual.com.

Coryat, Thomas. Coryat's Crudities. J. Wilkie, 1776.

Crowfoot, Elisabeth, Frances Pritchard and Kay Staniland. Textiles and Clothing c.1150-c.1450. Boydell Press, 2002.

Davey, Richard and Martin Andrew Sharp Hume. The Nine Days' Queen: Lady Jane Grey, and Her Times, Methuen & co, 1909.

Florio, John. Queen Anna's New World of Words. Printed by Melch, Bradwood. 1611

Frick, Carole Collier. Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes, and Fine Clothing. Johns Hopkins Univerisity Publisher, 2005

Girotti, Eugenia. La Calzatura aka Footwear. Bella Cosa, 1996.

Grew, Francis, Margrethe de Neergaard and Susan Mitford. Shoes and Pattens: Finds from Medieval Excavations in London. Boydell Press, 2004.

Hall, Joseph. Virgidemiarum, Six Books of Satires. Ed. J. Pratt, 1808.

Hazlitt, William Carew. The Venetian Republic. A. and C. Black, 1900

Hurlock, Elizabeth B. The Psychology of Dress. Ayer Publishing, 1984.

Lewis, Robert E. Middle English Dictionary. University of Michigan Press, 1983.

Marston, John. The Works of John Marston. J.R. Smith, 1856.

Moryson, Fynes. An Itinerary Containing His Ten Yeeres Travell Through the Twelve Dominions of Germany.. The Macmillan company, 1907.

McDowell, Colin. Shoes: Fashion and Fantasy. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1989.

Niccoli, Bruna and Landini, Roberta Orsi. Moda di Firenze, 1540-1580. Lo stile di Eleonora di Toledo e la sua influenza. Pagliai Polistampa, 2005.

O'Keefe, Linda. Shoes: A Celebration of Pumps, Sandals, Slippers & More. New York: Workman Publishing, 1996.

Pratt & Wooley. Shoes. V&A Museum, 1999.

Puttenham, George. The Art of English Poesy. Ed. Philip Sidney and Gavin Alexander. Penguin Classics, 2004.

Rabelais, Francois. Five Books of the Lives, Heroic Deeds and Sayings of Gargantua and Pantagruel. Trans. Thomas Urquhart and Peter Anthony Motteux. Project Gutenberg #1200, 2004.

Semmelhack, Elizabeth. On A Pedestal: From Renaissance Chopines to Baroque Heels. A Bata Shoe Museum publications, printed by Moveable, Inc., 2009.

Sewell, Elizabeth. Popular history of France, to the death of Louis xiv, 1876.

Shakespeare, William. Hamlet: A Specimen of an Edition of Shakespeare (William Caldecott contributing). 1832

Vecellio, Cesare. Habiti antichi, et moderni di tutto il Mondo. Dover Publications, 1977. Original woodcuts in 1598.

Walsh, Marcus Walsh . Shakespeare, Milton and Eighteenth-Century Literary Editing. Cambridge University Press, 1997.